Reading the Room:

Articulations of the Third Place in the Bookstores of Buenos Aires

A Senior Capstone by Julia Amsterdam

Introduction

I walk into el Ateneo Grand Splendid at 4:30 pm on a Wednesday. Located on Avenida Santa Fe in the upper-middle class part of Recoleta, the bookstore is surrounded by the European-influenced architecture and designer fashion stores that have inspired Buenos Aires’ controversial reputation as “the Paris of South America.” El Ateneo fits right in. A suited security guard greets me by asking if I am bringing any outside books, and marks those I show him with small white stickers that instantly flutter off when I go to put the books back in my bag. As I walk farther through the display tables of children’s books and calendars, the vestibule opens up to the main floor which is filled with hundreds of lights, framed by a red velvet curtain, and embellished with golden trim, all left over from the bookstore’s days as a 1920’s-era theater. The ceiling is adorned with a famous 20th century fresco by Nazzareno Orlandi, an Italian-Argentine painter, that depicts a series of elegantly robed people whose skin matches the color of the pale morning clouds that swirl behind them. Over 80 years prior to the opening of el Ateneo, the building opened as Teatro Grand Splendid in 1919. The theatre subsequently went through a series of shifts, serving as the production facility for a radio station and then as a movie theatre, until its reopening as a bookstore in 2001. While el Ateneo is a chain that operates at four locations, the Grand Splendid is by far the most elaborate and heavy in foot-traffic; commonly regarded as a must-see tourist attraction of Buenos Aires, it has about one million visitors per year.

The bookstore consists of four levels: the lower level, the main floor, and two upper levels that formerly served as balcony seating for the theatre. As the two upper floors are both narrow U-shaped balconies, nearly everything and everyone is visible at any given angle, both on the main floor and the upper- levels. The visitors line the railings that border the two upper-levels in order to take pictures of themselves inside what National Geographic named 2019’s Most Beautiful Bookstore in the World.[1] In the article, National Geographic refers to el Ateneo as “tucked away in the Recoleta neighborhood,” implying that it is inconspicuous, perhaps a well-kept secret of the city; in fact, whenever I mention my work to anyone in Buenos Aires, they uniformly ask, “ya fuiste al Ateneo?” [Have you been to the Ateneo yet?]

While this branch of el Ateneo is known best for its impressive and historical architecture, it also has a vast selection of books from all genres typical of a general bookstore. The main floor of el Ateneo is donut-shaped, serving as another balcony to follow the escalators down into the entrance of the children’s section on the bottom floor. The walls of the main floor and upper levels are lined with books, and the main floor also has a maze of large black shelves that follows the curve of the center, leading to the café, framed by velvet curtains, that once was the stage. Pablo, a tall white man with a gray-speckled beard, approaches me after he overhears me explaining my project to another man and is eager to share his perspective. We sit down in the café, planning to feign interest in ordering a coffee, talk, and then leave before the waiter tries to take our order. Pablo tells me he is a doctor from Patagonia in the south of Argentina. He is able to travel a lot por suerte [luckily] and likes to come to Buenos Aires three times a year, paying a visit to el Ateneo every time, “because it’s a peculiar place” due to its history as a theatre and its architectural structure.

The theatre layout is perfect for surveying a store; as in a panopticon or some shopping malls, the guards have a bird’s-eye view of the main floor and can keep watch without people realizing how surveilled they really are. There is even a central balcony above the vestibule where spectators may once have gathered during intermission. I watch as it is used as a method of surveillance by a guard who looks over the shoulder of an unsuspecting customer from the balcony above her as she skims the Spanish edition of Becoming by Michelle Obama, Mi historia, oblivious to the fact that she is being watched from above. I make eye contact with the guard and am first to look away.

The few and highly coveted comfy chairs reside in a gap between the shelves on either side of the center and in the side box seats. They are never empty for more than five minutes. Mostly, the chairs are occupied by seniors, quietly reading their way through the stack of books placed on the table in front of them. One of the chairs becomes empty and I fight the urge to sprint to it from across the room. Walking quickly, I reach it before it is taken and sit down next to two men who look to be in their sixties.

Once I get over my awe of the fresco and the gold-trimmed balconies dotted with bright lights, I am able to relax and begin to notice how the bottom floor bustles with visitors browsing the shelves and trying to shuffle past each other, many taking selfies, or pretending to read a book for a photo. It is time for la merienda, the late-afternoon snack, and the café begins to fill. People sit in the café area, reading or chatting, while eating toast with butter and jam. The main floor’s open pathways become congested as people both depart and enter, some pausing abruptly to take a last-minute photo. A low and constant hum of conversation fills the store, drowning out La Vie en rose that is playing overhead.

I focus again on the two security guards, now communicating with each other via walkie-talkie while making eye contact from different floors. The guards are stern-faced, one gesturing emphatically with his hands as he speaks. What is he mad about? I think they’re just gossiping. They seem very invested in their conversation and their walking pace changes depending on the intensity of their response. Every so often, I see them correct someone’s behavior: don’t put your feet up on the table, you can’t take notes here, don’t sit on the ground.

As the buzz of conversation becomes increasingly impossible to ignore, I turn to the man next to me and ask in a whisper what he is doing here. He says he comes here every day. I ask him why, and he responds, “es mi tiempo dulce” [it’s my sweet time].

⬥◈⬥

As the city with the most bookstores per capita, a vital part of the identity of Buenos Aires, Argentina is rooted in the importance of literature throughout the city’s history and the country’s. The Republic of Argentina’s education system was standardized by President Domingo Sarmiento in the late eighteenth century. Sarmiento’s principle objective was mass education, believing that the higher the education level of the citizens of Argentina, the higher their socioeconomic status and quality of life, which would result in “the development of a free and sovereign nation” (Bravo, 1994). Mass education extended to mass literacy, as he also established free public libraries across the country (Crowley, 1972). This helped to instill value in literature on a state level in Argentina which promoted the prominent literary culture seen today.

For Laura Podalsky (2004), 1965 was a particularly important year for Buenos Aires, the “the Year of Argentine Literature,” to quote the magazine Primera Plana. That designation alluded to a boom in the production and publication of literature by Argentine authors and to its “blossoming” readership (Podalsky, 148) that worked to promote new ways of being porteño (being from Buenos Aires, a port city). Podalsky notes that Primera Plana celebrated this emergence of Argentine literature as embodying the magazine’s goal, “to represent the ‘public’s’ concerns and contribute to the renovation of Argentine civil society” (149). In addition, large publishing houses like Editorial de la Universidad de Buenos Aires (EUDEBA) began to publish books at an increased rate, publishing the same work in multiple versions of different material quality in order to appeal to a wider audience of readers. EUDEBA also opened up a series of kiosks around the city for readers to buy their books on-the-go, establishing different venues for engaging with books: the bookstore for “deliberate consumption” and the kiosk as a site for a “spontaneous purchase… [by] a random passerby” (153). Podalsky notes that the accessibility of the kiosks put some people on edge, as they feared for the future of “high culture” if, as writer Victoria Ocampo notes, “the common man buys works by Cortázar and roams about with them in a Torino or on the subway or a bus” (153). Certain literary and cultural critics appeared to act as gatekeepers to high culture, however it was also noted that the consumption and appreciation of literary works by the famous Argentine authors indicated an elevation of cultural taste.

Primera Plana began to set the standard of taste for middle-class Argentines by releasing monthly bestseller lists curated through working with certain bookstores to see which books had the highest sales. However, as Podalsky observes, the magazine only included bookstores in the downtown areas that are frequented primarily by affluent people. Therefore, through the preferences demonstrated by bookstores in middle-class neighborhoods, the magazine established a standard taste for Buenos Aires, and ultimately, Argentina as a whole.

From 1976 to 1983, Argentina experienced a brutal dictatorship under Jorge Rafael Videla, in which an estimated 30,000 people were disappeared, arrested, and murdered by the regime. The dictatorship enforced harsh censorship of all print media and art forms including newspapers, books, plays, and movies. The scope of this essay will not address the effects the dictatorship still felt in the city decades later, as my research did not lead me in that the direction, but this does not mean that the dictatorship is not prevalent in the culture today.

Since the fall of the regime, the last few administrations have each had different policies on the role of culture in the nation. In a summary of the change in cultural policies in Mexico and Argentina, Elodie Bordat-Chauvin (2016), a political sociologist, observes that in Argentina, “cultural policy is less institutionalized and more dependent on politics” (3). Raúl Alfonsin, the first democratic president of Argentina after Videla’s rule promoted the “democratization of culture,” believing that cultural forms like art and books should be accessible to all citizens. After him, Menem, who was known for the adoption of neoliberal policies promoted, “culture as an economic resource,” meaning that “Argentines were invited to read and therefore buy books, to see art exhibitions and then buy art pieces, and so on. The role of culture as a symbolic creator was left aside for its entertaining and economic role” (9). For President Kirschner, neoliberal policies had less influence, as his administration shifted away from culture as an economic resource and towards its potential for “reconstructing social cohesion” and establishing “a sense of belonging to the nation” (17). Through these various policies, the consumption of culture through activities like buying books has come to be considered the means to establishing social cohesion and national identity by the Argentine state.

Reading is often considered a way to get out of one’s self, a way to seek comfort from the problems and hardships that come with life. An article published in the Guardian, “A novel oasis: why Argentina is the bookshop capital of the world,” includes a photo of the famous Ateneo Grand Splendid and its many bright lights as the main image. The first line of the article attempts to answer the question posed in the title: “Their country has endured military dictatorship, economic collapse and a particularly vituperative brand of politics, so perhaps it is not surprising that Argentinians should still find solace in the oldest of pleasures: curling up with a good book” (The Guardian, 2015). The bookstore, in this argument, serves as an entry point to alternative worlds into which readers can escape, the act of searching for the next book to read almost an escape itself.

However, I am not convinced that the bookstore and, by extension, reading operate solely as escapism for the Argentine reader-consumer; rather, reading can be a confrontation with difficult realities. Luisa Velenzuela, an Argentine novelist, writing in a New York Times article published just three years after the dictatorship, claims that literature is what will revive Argentina in the wake of the brutality of the regime: “For the people of Argentina, writing has become a form of catharsis… There seems to be a public awareness that only by naming the terror can we avoid being terrorized again” (The New York Times, 1986). Indeed, when I asked my interlocutors why they read, many answered that reading teaches them how to think and exist in the world.

The third place, a term coined by Ray Oldenburg in his book The Great Good Place: Café’s, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community, is a place outside both the home and the workplace where people can build relationships with each other by spending time together and making conversation. Oldenburg utilizes several historical and contemporary spaces emblematic of the third place, naming the coffeehouse in Vienna and England, the bistro of France, and the American pub as prime examples. Eight characteristics define the third place. First, the space must be considered neutral ground, meaning that no one is obligated to be there and participants can come and go as they please. Second, the space must be a leveler, meaning that it levels individuals out so that social and economic standing are not of significance to others. Third, playful conversation should be the main activity. Fourth, the space must be fully accessible and accommodating to all that convene there. Fifth, the space must have regulars who also attract newcomers. Sixth, the space should not be too elegant, and should maintain a low profile. Seventh, the tone of conversation must always be amiable. Finally, the space must be thought of as a home away from home, meaning that there is a felt sense of belonging.

While characteristics of the third place are achieved in bookstores, it is not possible for a third place with all of Oldenburg’s original conditions present at once to exist in Buenos Aires. Larger factors such as economic insecurity, class stratification, gentrification, and neoliberal policy affect the social and spatial layout of the city in ways that limit the possibility for third places to be established.

I argue that the notion of the third place must be more flexibly understood to accommodate these shifts. Inasmuch as large social and economic factors affect the concepts of home and work, it is necessary to consider how these factors may shift the significance of the third place as well.

I will investigate how the booksellers of several Buenos Aires bookstores use their respective literary tastes to carve a space for themselves and their aspirations, illuminating how they embody aspects of Ray Oldenburg’s idea of the “third place” as Argentina’s economy and political atmosphere continue to fluctuate. Through the use of cultural hierarchies of taste, the booksellers and their bookstores move both with and against the neoliberal and political shifts the city has been experiencing since the nineties.

Distinction and the Third Place

As I pull open the heavy iron door and step into the store, the whirring of motorcycles and buses speeding up and down the busy avenue outside fades as the sound of Western classical music fills my ears. Patricio would later tell me that the choice of music is deliberate. He wants his bookstore to serve as a “refuge from the craziness of everyday life,” and drowning out the sounds of busy rush hour traffic is vital to complete the experience. While his choice of Western classical music amuses me with its Eurocentric connotations, I feel calmed by the music as it does indeed help me tune out the roar of buses outside. I’ve come early for our interview so I can get a feel for the space of the store and its books; following other customers, I stroll counterclockwise around the store, slowly, so as not to disrupt the rhythm and accidentally cut someone off. Patricio is seated in the back left corner working on his laptop. As his right hand moves and clicks with the mouse, his left, raised above his head, conducts the music that streams out of the stereo in front of him.

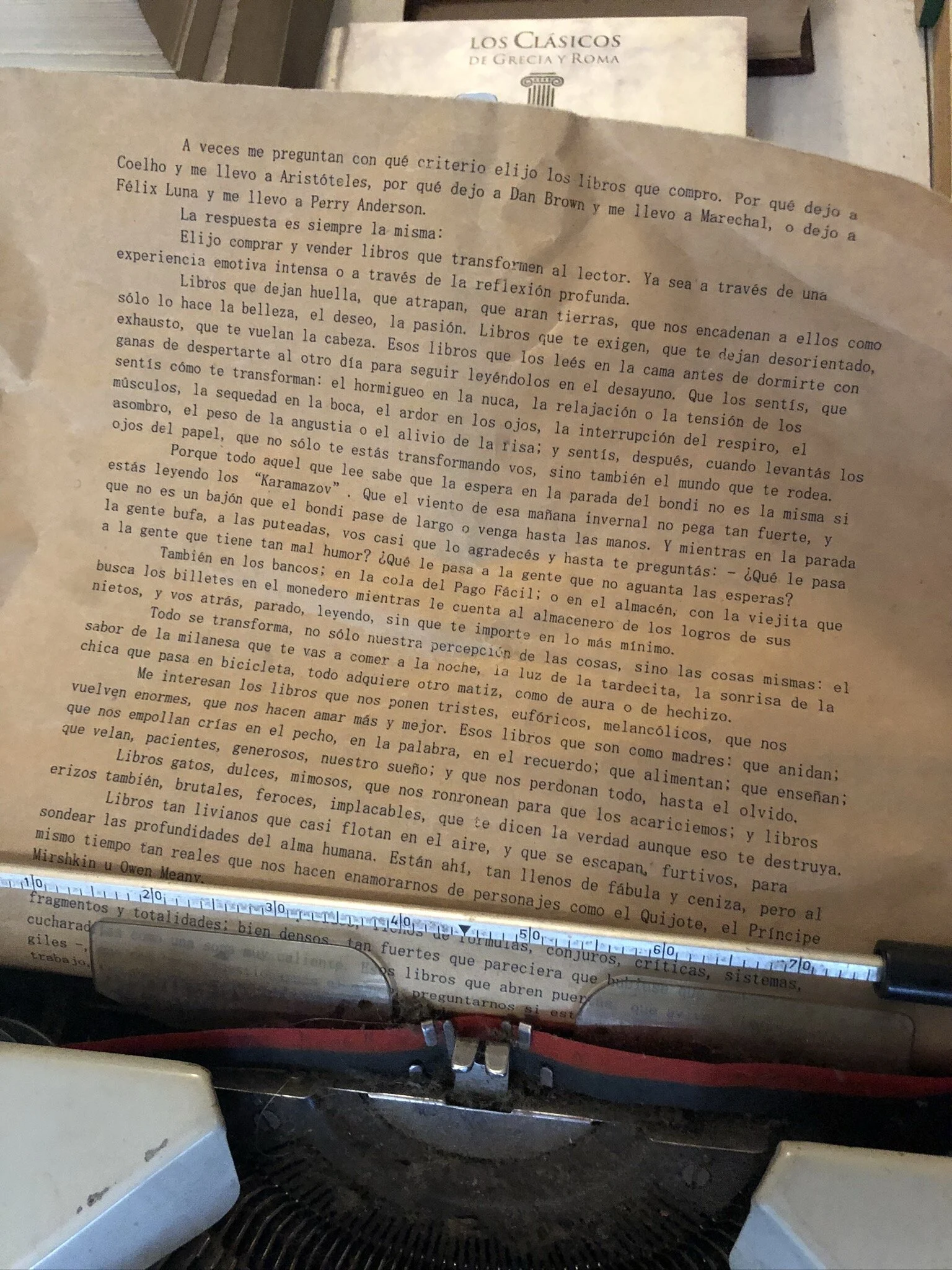

“Take a look at the center table. I’ve put out my recommendations for literature and philosophy. Let me know what you think.” I do as he says and turn my attention to the long wooden table that splits the room in half. The table is crowded with uneven stacks of books, its white surface visible only in the occasional vacant space where a book once was. I move around the table, sifting through each stack. I feel almost as if I am in a race with my fellow customers to see what’s in each stack, worried that someone else will find something good before I get the chance. The books he has selected for display exhibit no discernible trend, jumping from century to century, country to country, the only common denominator is that he thinks they’re good. Atop the table, underneath a stack of pamphlets, sits a typewriter with a brown, crumpled piece of paper resting idly in the carriage. I move the papers to the side and lean in close to read the faint black font of the typed out paragraphs:

“A veces me preguntan con qué criterio elijo los libros que compro. Por qué dejo a Coelho y me llevo a Aristóteles, por qué dejo a Dan Brown y me llevo a Marechal, o dejo a Félix Luna y me llevo a Perry Anderson.

La respuesta es siempre la misma:

Elijo comprar y vender libros que transformen al lector. Ya sea a través de una experiencia emotiva intensa o a través de la reflexión profunda”

[Sometimes people ask me how I choose which books I buy. Why do I take Aristotle, but not Coelho, why do I take Marechal instead of Dan Brown, or Perry Anderson instead of Félix Luna.

The response is always the same:

I choose to buy and sell books that transform the reader. Whether through an intense emotional experience or through deep reflection.]

Aristipo Libros is a used bookstore in the Villa Crespo neighborhood of Buenos Aires. Patricio, the owner, started selling books out of his home ten years ago through the website Mercado Libre; when his business became successful, he decided to open his own store. To stock the store, Patricio purchases used books at fairs and online, choosing only the titles that he deems worthy of reselling. As I sit with him in a folding chair by his desk and watch the customers move through the store, he tells me he rejects the majority of the books offered to him. “I only sell the books that I think are worth it [vale la pena] for people to read,” he tells me. While Patricio admits that he has not read all of the hundreds of titles that he sells, he claims to have read the vast majority or uses a well-tuned intuition to determine what to buy. Patricio, in this way, is seeking to profit off of his book expertise (he is a writer himself with a degree in literature from the University of Buenos Aires), as the store is a rotating selection of his recommendations, and a very carefully curated one at that. He immediately asserts his literary taste on the typewritten page, where he uses the names of famous authors to distinguish those whom he deems worthy to sell from those he does not. The authors he names, Coelho, Aristotle, Dan Brown, Marechal, Félix Luna, and Perry Anderson, exist, to him, on opposing sides of a line between high and low taste that he assumes the reader can follow regardless of whether they agree or not. Patricio distinguishes his taste in books from that of others by using these “famous” authors’ names, following the process of self-definition that sociologist Michele Lamont (1992) defines as “the process by which individuals define their identity in opposition to that of others by drawing symbolic boundaries.” Informed by the connotations of his own positionality, he inscribes a cultural hierarchy in the stock of his bookstore, assuming, however accurately, that the people who come into his store will also recognize these authors and their place in literary culture, and be able to see the hierarchy for themselves.

With respect to the act of choosing books, he explains, “my job is to rescue and distribute good literature, then to recommend those authors too” [emphasis mine]. Though I do not ask him exactly how he defines good literature, he explains: “The type of books I propose to read are the books in which the author works with language, with trauma, with different literary devices so that the experience is rich, complex, complete and transformative” as opposed to the “immediate satisfaction” granted by los bestsellers sold in bookstore chains.

I watch as Patricio reifies this hierarchy when an older woman with wispy blonde hair approaches the desk to ask if he has anything in stock by Isabel Allende. He responds matter-of-factly, “No, I don’t carry her work.” The woman expresses her disappointment, saying that she wanted to buy a book by Allende for her daughter. When I ask him specifically why he does not carry authors such as Isabel Allende, he responds, “there is a certain type of literature, novels, (like) bestsellers, that seem, to me, to be for a specific type of public. It’s a type of reading that doesn’t seem enriching to me.” While I think that Isabel Allende’s works are quite enriching, I do not attempt to argue with him, as he understands his opinion to be an objective truth, not a subjective one.

I find Patricio’s judgment to be slightly contradictory. While on one hand, he does not see any value in los bestsellers, he also cites canonized popular authors such as Jorge Luis Borges, William Faulkner, and Juan Rulfo as examples of enriching literature. Despite how the three authors are rather mainstream names in the literary world, they still exhibit all of the qualities that, to him, denote good literature.

However, his aversion to los bestsellers is not necessarily because they are popular, but because their popularity is due to how accessible they are. This in accordance with Bourdieu’s (1993) observation that, within the cultural field, that which gains economic success, be it a book or piece of art, is perceived to be “selling out.” In other words, Patricio believes that if a multitude of readers are able to enjoy a book on a large scale, it is because the book does not challenge them. In this way, Patricio asserts a version of “high taste” (Bourdieu, 1987), one that elevates works that, to him, encourage thorough contemplation in the reader.

In opening a bookstore that sells only the books he feels are worth reading, Patricio is uniquely straightforward with his preferences, but the preferences themselves are by no means uncommon. Indeed, the way in which Patricio distinguishes high and low culture is reflected in Bennett, Emmison, and Frow’s (2013) findings regarding reading culture in Australia. Through interviews and questionnaires, they surveyed Australians’ taste in books, art, television, and other forms of media and cultural intake to determine what types of patterns of cultural participation there are in Australian everyday cultures. Their findings regarding reading culture demonstrate that the distinction between high and low taste utilizes the same rhetoric of “enriching” or “frivolous” in a way that is also strongly gendered and classed. The survey results define reading as a “gendered practice” (148), as genre preferences depended more on gender than on class or education, for while women read books of all kinds, men were much less likely to read the genres that were regarded as more feminine. For survey takers, the distinction of high versus low as enriching versus frivolous was conflated with masculine versus feminine ways of reading, as women “condemned themselves as frivolous readers, both for reading idly, as a diversion, rather than, as the terms in which they typically contrasted men’s reading with their own, for a particular purpose” (148). Patricio does not explicitly assert a lack of interest in female authors or feminized genres. However, in his definitions of good literature as one that challenges the reader and bad literature as one that does not require any active effort to appreciate, he participates in the system that splits literary genres, and subsequently their readerships, into being either purposeful or frivolous, and by extension, masculine or feminine. Between the high genres that enrich their readers and the low or popular genres that do not, his idea of a “certain public” that lacks the literary taste he respects is encoded in gendered and classed language. Mass-marketed books that are plot-focused (los bestsellers), like romance novels, have historically been marketed towards women as forms of entertainment. These stand in contrast to the more challenging, contemplative literature that Patricio finds valuable for its ability to demand the attention of the reader and, in turn, reward them. By only stocking the store with the latter, Patricio establishes Aristipo as a space for aesthetically high-class and masculine expressions of taste.

Patricio’s use of Western classical music helps to establish an immediate atmosphere of an elite, exclusive space, as the musical genre connotes the same artistic high taste he feels the store is stocked with. His intention to create a refuge for his customers is about creating an atmosphere apt for the concentrated, contemplative attention that the “good literature” he stocks his shelves with requires. As mentioned above, he wants his bookstore to serve as a “refuge from the craziness of everyday life,” and drowning out the sounds of busy rush hour traffic with the music streaming from the store’s speakers is vital to complete the experience. In addition, it is one of several aspects of the environment he hopes to establish that, in turn, resemble certain characteristics of the “third place.” Patricio’s distinguishing the environment of Aristipo from that of the busy city avenue corresponds to Oldenburg’s analysis of the third place as a type of refuge from everyday life. Whereas many consider the third place as mainly providing an “escape or time out from life’s duties and drudgeries,” Oldenburg asserts that “the escape theme is not erroneous in substance but in emphasis; it focuses too much upon conditions external to the third place and too little upon experiences and relationships afforded there and nowhere else” (Oldenburg, 21). For Patricio, Western classical music is vital to the notion of refuge, as it sets the tone for the type of attention that he believes the books he sells demand.

As I sat in the low-seated fold out chair next to his desk, which doubles as the cash register, we were interrupted several times by customers trying to make a purchase. He was familiar with each of the purchases and would make friendly conversation as he rang up people’s orders. The conversation ranged between quick, warm small talk, and longer, more thoughtful discussions. He would frequently respond that he did not stock anything by certain authors, but, in one case, the mention of an author’s name excited him so much that he recited a lengthy passage from memory in response. One woman’s purchase inspired an hour-long discussion on the importance of reading, with several other customers joining, piles of books sitting heavy in their arms. No one exchanged names, but people were quick to talk about their favorite books, or the writing workshop they attend on weekends. When Patricio and I spoke later, I commented how nice it was that people stopped to talk so often with him and the others in his store. He agreed. “It’s important to me that people can find a sense of community here,” he said, “and talk to people that they might not otherwise meet. Reading can sometimes be an isolating experience, so I hope that when people come in to get a book, they can also have a conversation. Everyone has a shared interest here.” Patricio establishes his bookstore as a third place, first through the change in ambience and then through encouraging his customers to talk to him, and by extension each other. Despite his sitting apart at a low desk in the back of the room, his investment in talking to his customers sets the tone for the environment as a whole, as throughout my two hours there, many people crowded around his desk to talk about a particular author or how many books one reads a year.

Bookstores are used in different ways depending on their patrons and the space itself, and most shift in and out of qualifying as a third place. Indeed, Aristipo manifested an environment in which customers felt the urge to stick around, despite having only one comfortable reading chair. This is common in many independent bookstores, as the size of the store itself and consequent lack of chairs and general free space do not permit many people to linger comfortably. Similarly, many customers walk into a bookstore and head straight for the nearest bookseller in search of a particular book. If it is in stock, a purchase is made; if not, the customer most often leaves without looking for another. While most people tended to join Patricio and fellow customers in conversation, I did see others walk in, ask for a book, and either buy it and leave, or leave empty-handed.

Indeed, many booksellers I spoke with articulated a desire for their customers to spend time in their stores, to look around and skim through some books, or even to sit and talk for a while. They complained that, instead, many of the customers tend to treat the experience much as they would a quick run to the grocery store (Auge, 2009). A bookseller in a larger bookstore, one with a big leather sofa, a rarity even in multi-level bookstores, expressed his frustration with how little time many customers spend in the store, only coming for bestsellers or expecting him to be ready with recommendations. “One time,” he tells me, “a woman wanted me to find a book she would like while a taxi waited for her outside.” This sense of urgency in the customers was apparent to me and reinforced my reluctance to approach them. Many of the conversations and interviews I conducted in bookstores were preceded by several minutes of perambulating the store, “to get a feel for the space,” when really I was trying to gather the courage to interrupt someone’s book shopping in order to ask them how they felt about it. The pattern noted above, in which customers spend only the time necessary to ask the bookseller for a book, buy it, and leave, made any attempt at conversation more difficult to justify on my part.

On a late Wednesday afternoon, prime time for post-work book shopping, I sat in the back of Waldhuter books on the same black leather couch with Joirge as he lamented the brief time customers spent book shopping. He had started his career as a book vendor in the eighties, and I valued his decades of experience and perspective on how the consumption of books and bookstore spaces may or may not have shifted. Upon my asking him how the customers have changed over time, he told me: “Before, there was more time. One could work, come into the bookstore, spend a half hour or forty minutes talking to the bookseller, or not, look at the books, ask for a recommendation, et cetera. Now, in many cases, unfortunately, everything must be fast.” Waldhuter books is situated on Avenida Santa Fe, one of the busiest and most luxurious shopping streets in Buenos Aires. Whereas Aristipo books is located in a calmer residential neighborhood, Waldhuter is in a central shopping location sandwiched between shoe and clothing stores that perhaps inform the shopping mindset that customers bring in with them.

While a central characteristic of the third place is the sense of escape and refuge from everyday concerns, the rush to get from place to place often felt by people in cities such as Buenos Aires makes it increasingly difficult for the kind of third place that Oldenburg imagined to flourish. Several external factors influence how a customer may consider using a space that do not include (but likely contribute to) their everyday worries such as the shortening of leisure time, to which Joirge referred. Whereas Oldenburg presents several examples of consumption spaces that operate as third places, the atmosphere seems to be getting more and more difficult to achieve. My conversations with booksellers suggest a desire on their part for their bookstores to embody at least some of the characteristics attributed to the third place, as modern socioeconomic, political, and urban factors seem to be making that possibility less and less realistic.

In the wake of the economic crisis currently underway in the country, used bookstores have become many people’s main source for books, as new books’ prices have become increasingly expensive. Indeed, as a used bookstore, Aristipo’s prices are significantly lower than those at a bookstore that sells new bestsellers. In theory, while his price range allows for high literature to become more affordable, access depends as much on cultural as economic resources; the individual’s background and tastes are what make the store’s literary commodities truly accessible. With respect to the relationship between reading, class position, and education, Accounting for Tastes notes that, “literary forms of cultural capital are most strongly associated with… the degree to which both the acquisition and maintenance of their class position is dependent on the certified intellectual competencies they have acquired through the education system” (169). While the economic costs of the used books at Aristipo are relatively low, Patricio’s adherence to his notions of high and low literature through the stock of the store reifies a pre-existing cultural hierarchy that actively limits who can claim access to the type of literature that he sells.

[1] The decade that saw the highest influence of neoliberal policies under Menem’s administration, in which “Argentines were encouraged to “read and therefore buy books” by the state in efforts to mine “culture as an economic resource” (Bordat-Chauvin, 2016)

The kioskos [stalls], in contrast, sell both los bestsellers and “good” literature (according to Patricio) that is used and for cheap. Whereas indoors bookstores feel like their own world, quietly controlled and controlled to be quiet, the stalls are right in the middle of one of the more mundane yet hectic parts of daily life: rush hour transit. My friend and I walked through them one Sunday afternoon on the way to hang out at los bosques de Palermo, the big nearby park. Excited to learn about more bookstores, I had asked my friend if they were there every Sunday, and he told me that the kioskos were open every day. At that point, I had lived about four blocks away for over a month and hadn’t ever noticed them, despite walking by dozens of times.

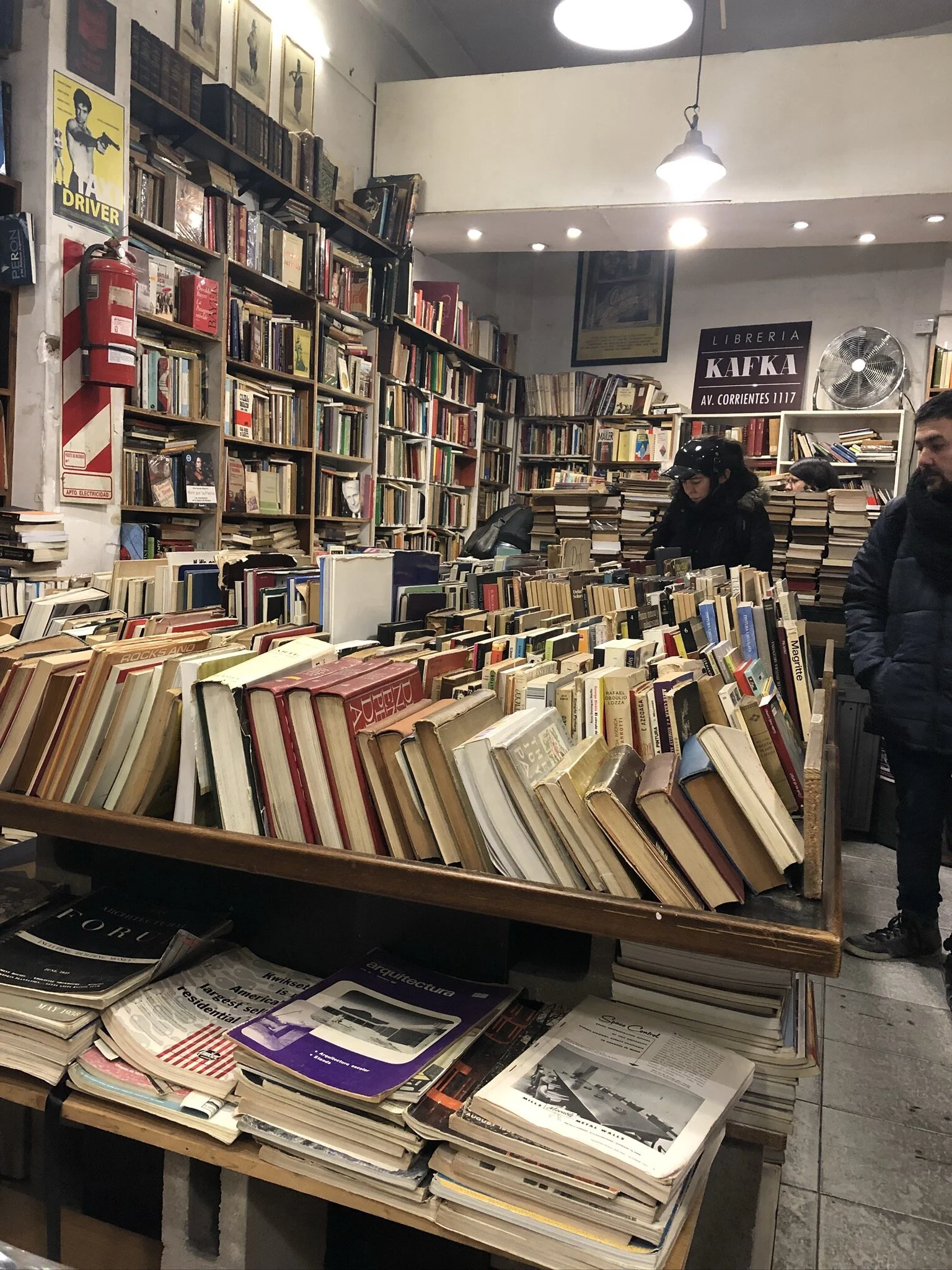

These are the same kioskos that were believed to have threatened the future of high culture in the eyes of the culture writers of 1965 (Podalsky, 2004). There are about 21 stalls in total facing the street in two rows on a concrete island that stretches between the opposing traffic of Avenida Santa Fe. The kioskos themselves are small, only big enough to fit their owners and stocks of books. They set up the display of books and take it down at the beginning and end of each day, using tables to put books right in front of their stall and across the walkway. The booksellers each have their own corners to sit or stand inside the stall with mate (yerba mate) and thermoses nearby. Some are more withdrawn on their phones, and some are seated, ready to ask passersby, “qué buscabas?” “What are you looking for?” If you’re walking fast enough, you can hear this question as many as five times in under a minute until they eventually see you are just passing through.

I often had to interrupt the people I was speaking to because I couldn’t hear them over the sound of the buses speeding to the stop 30 feet away. My ears were saturated with the very sounds of everyday life that Patricio feels necessary to mute with Western classical music. In the midst of rush hour traffic, the kioskos, were a third place within the context of a non-place (Auge, 2009), one that people actually use to get between home and work, the means through which they get from one place to another, that isn’t a destination in itself. The kioskos are similar, in that their structure inspires the quick purchase of a book en route to somewhere else. It does not fit many conditions of the third place, for while it is more economically accessible, it would not be considered a refuge on Oldenburg’s terms.

After I walked around the whole of the stalls a couple of times, I stopped to talk to a couple of the booksellers. Juan, a bookseller with whom I spoke, had worked in the kioskos for forty years, starting young with his dad at another location. I asked him about the reading patterns of the city and how they had changed over the decades he had worked there. With clear frustration, he explained that he felt that people did not value books as much anymore, not like they did in the 1990s:[1] “Now people feel comfortable asking me for discounts. I sell used books, there is already a discount!”

Here, Juan expresses a similar type of disillusionment as Joirge, who lamented the lack of time his customers had to spend in his store. Both perceive this type of treatment of books by their customers as an index of the devaluation of their craft. Patricio’s bookstore is set up in a way in which he will never encounter this; however, he was measuring with respect to the quality of the literature itself, as opposed to the quality of attention that people afforded books in general. Joirge exhibited a milder version of Patricio’s frustration with respect to los bestsellers, for he felt as though his customers wanted just any book they heard was good, as opposed to getting a carefully curated recommendation that came with his 20 years of experience. Juan, with four decades of experience, felt frustrated by his customer’s economic devaluation of the books he sold in the wake of how little he felt people were reading.

Their resentment is demonstrative of the concept of “heroic resistance to a decline in the nature and the position of the literary” that Janice Radway (1997) notes formed in reaction to mass production and standardization. These three booksellers, although coming from different stances, unite in opposition to mainstream print and in criticism of how their customers place value on books. In “Eating local in a U.S. city: Reconstructing ‘community’—a third place—in a global neoliberal economy” (2011), Gagne observes that farmers and shoppers at a farmers market in Washington D.C. establish a third place through a devotion to farming and shopping local to ultimately resist the domination of supermarkets and the economy. This devotion, Gagne explains, is a shared ideology between farmers and shoppers that is the root of the construction of the farmers market as a third place. In this way, Radway’s notion of “heroic resistance” serves as an ideology that connects booksellers and customers under Buenos Aires’s neoliberal economy, as the devotion to share in appreciation and purchase of books of the booksellers’ tastes establish bookstores as third places.

The Bookstore-Café as an Alternate Home

One evening in late June, I went to my friend Jose’s house a few blocks up from Libros del Pasaje on Thames for an asado [barbecue]. I had met Jose back in November at another of his asados, and knew I was in for an amazing meal, good music, and people from all over the world. Jose, a blonde, twenty-something Argentine, rents out rooms in his grandparents’ large home in Palermo and only accepts payment in Euros and American dollars. I was feeling exhausted and frustrated, having spent the day going from bookstore to bookstore in San Telmo, the oldest neighborhood, and finding all of them either closed or empty. My close friend would not be coming to the asado until later and I was mentally preparing myself to socialize in Spanish on my own. This semester, the rooms in Jose’s house were rented out to French people who were all crowded around the big wooden table in the backyard sipping wine when I arrived. I put the bottle of Malbec I had brought on the table and introduced myself to everyone. The six French women all spoke English with me, but slowly transitioned back to French as my best effort at small talk petered out. An hour later, stomachs full of wine and choripanes, the group was scattered throughout the backyard, as music pulsed. Feeling reenergized, I struck up a conversation with Gigi, a French woman who spoke fluent British-English with contagious enthusiasm. We talked for a while about her dream job of inventing perfumes, something I had never thought of myself, and she asked me what I was doing in Buenos Aires. I explained that I studied Anthropology and was there to do research for a project on the city’s bookstores.

“Oooh, yes! I LOVE the bookstores here!” she exclaimed. “My favorite one is just a few blocks away!”

“Is it Libros del Pasaje?” I asked. The anxiety from my unsatisfying day dissipated as I absorbed her excitement for bookstores.

“Yes!” We bonded over the fact that we both went there multiple times a week and that there was a high chance we had been there at the same time. I shared that I loved to take a lap around the bookstore to look at all of the books after sitting in the café for a while, and she told me she did too, “even though I don’t even read that much.” She added that she’d never bought any books at the bookstore, but loves the idea of, “being surrounded by books [as I do my work].”

On the other hand, I love to read. My passion for reading is the main reason why I loved going to the café in Libros in the first place, and it is the main reason why I was initially so fascinated by the quantity of bookstores in Buenos Aires that would eventually inspire me to do this project. The main café area is constructed from what was once the outdoor patio of the former caserón, hence the current glass pane roof. The families would be able to access the patio through several window-paned doors on three of the four walls. Excluding the café’s official entrance in the back, the former doors now serve as windows between the café and the store. I would often pause what I was doing to look through these windows and marvel at the walls of bookshelves, feeling inspired simply by being in proximity to them.

Prior to leaving, I would always spend some time in the bookstore, going from shelf to shelf, display to display, touching the covers and opening them to skim random pages. The thought of all the great books I could read someday gave me a rush of excitement, similar to the excitement that Zukin (2005) observes we derive from our in-store interactions with products (her example being food) whether by touching, smelling or reading them. “We want to be around these things,“ Zukin continues; “often, we want to have them on our bodies and in our homes” (13). I wanted to read all of those books one day, and, while I only bought a book from there once, the sense of their abundance kept me coming back to the café.

Radway (1997) connects the excitement people associate with goods to advertising ideology “that bestows on commodities the ability to grant the desires of the consumer.” This enchantment of the commodity form “[created] a semantic and emotional penumbra surrounding the featured object [that] might then surround any customer who bought, used, or displayed that object” (149). In other words, advertising discourse has conflated the purchase of commodities with the cultivation and expression of the consumer’s sense of individuality. My love of reading does not require that I buy every book, as there are other ways of accessing literature; however, my interlocutors and I have mutually recognized owning a well-stocked bookshelf as something to strive for, most likely as a result of these processes. In fact, many American publishing houses in the early twentieth century discovered that “the very idea of the book and the cultural value attributed to it could confer status on its owners…” (Radway, 145) and used it to their advantage. Indeed, I have incorporated, admittedly with pride, my interest in literature as a part of my identity, and my love of books has extended to an interest in being in the spaces in which books are sold, regardless if I am doing any purchasing, for being surrounded by them is pleasurable in itself for me.

Gigi’s love for Libros de Pasaje is inspired more by the feeling she derives from being surrounded by books than the act of reading. In this way, she is not affected by how a particular book or the idea of being well-read may contribute to her literary taste, but rather through the socially acquired taste that the presence of books gives her feelings of pleasure even when they are just sitting on shelves. Radway illustrates the value of shelved books in her analysis of articles published in interior decorating magazines in which the authors advise readers to incorporate books into the interior design of their homes. By using books as decorations in order to make a space feel more welcoming or to add to its color scheme, the authors are, “searching for a way to understand books as aids to emotional response and mood construction” (151). Indeed, while the articles’ authors, Jane Guthrie and Margery Doud, are writing with an approach to home design in mind, they demonstrate how the shelved book as a commodity exerts agency, “as a magical, talismanic object capable of creating a mood and state of mind… simply by virtue of its presence in a room” (148). Like Doud and Guthrie, Gigi is attentive to the ways in which books as objects have been afforded agency to establish a particular mood or emotional state in their consumers. She sees the meaning that books carry and feels almost as if it somehow extends to her, or communicates something about her, by choosing to spend time among them and enjoying being in their presence.

⬥◈⬥

I’m in Libros right now. A woman, older, just began to listen to a [voice message] at full volume, oblivious to the people who look at one another knowingly, either rolling their eyes or giggling. I make eye contact with Cynthia, the woman sitting at a neighboring table. She is an eye roller. She shakes her head, saying “No lo puedo entender. NUNCA lo puedo entender” [I can’t understand it. I can NEVER understand it]. “Bookstores are for reading and relaxing,” she says, “not for socializing.” She tells me that while, yes, she’s on her phone[1] right now, she came here to read; she has books in her bag! Our conversation comes to a close, and she pulls out a bag of said books, which she puts on the table. The bag reads CÚSPIDE [the name of the most common bookstore chain in the city]. Buying a book from one bookstore and reading it in the café of another is okay, not great, but normal. To bring the book still in the other store’s bag, however, feels a bit wrong. Like eating takeout from one restaurant in another. Inappropriate. The books along with the Cúspide bag have since disappeared and the two iPhones remain. She has watched a snippet of a video at full volume before quickly pausing it and apologizing to me (twice!). Now she is reading a book on her phone.

Journal Entry, August 25, 2019.

This exchange took place only days before my return to the United States, after spending hours upon hours in my beloved Libros. I would sit in Libros as if it were my job. I went to Libros for my research. I went to Libros to read theory relevant to my research. I went to Libros to stop for coffee between bouts in other bookstores. I went to Libros to meet up with friends. I went to Libros to read for pleasure. I went to Libros to write in my personal journal. I have cried in Libros multiple times. Later in the same entry as the one above, I called Libros an “extension of my own home” because of how comfortable I was there. Too comfortable. It was a perfect place for me because I could do just about anything there and feel productive because I was technically in my field site, taking it all in as I hung out with a friend or wrote in my diary.

Both the bookstore and the café are classic examples of Oldenburg’s (1999) notion of the third place, as they both have historically provided a “neutral” place between home and work in which community-building and sociality can take place. There are high numbers of both in Buenos Aires and they have played large roles in the cultural history of the city, as many are now famous landmarks where prominent writers and thinkers were once regulars. The bookstore-café as a single place is relatively new in the city’s history, and they have become more popular in the last twenty years, as many of the newer bookstores, Libros included, now share the space with a café. While the two complement each other nicely, many of the booksellers I spoke to regarded the café as a way to make enough income to support the bookstore, which is particularly important as the country’s economy has been in flux since the crisis in 2001.

In a study of bookstore-cafés and their potential as third places in Hangzhou, China, Thuy Van Thi Nguyen et al (2019) write that bookstores in China play important roles as cultural and traditional agents because of their connection to the notion of reading as symbolic of high culture. Surveys of patrons were conducted in the bookstore-café to gather information on what the type of space may provide for patrons, and found that, as a result of its environmental qualities as being both a bookstore and café, the space is regarded as being perfect for both leisure and work. The writers observe that their research concluded, similar to Gigi, that “sometimes it is more important for consumers to spend time and browse through the bookshelves rather than simply purchase books” (231). The café and bookstore mutually enhance each other’s atmosphere, the presence of shelves stacked with books being key. Indeed, the same value that, as Radway writes, Jane Guthrie places in books as home decoration apply here. The “comfortable” environment she seeks to establish in her own home through the display of books is the same one that causes bookstore-cafés to give off a “homey” feel. This contributes to the bookstore-café’s function as a third place, in which the feeling of a “home away from home”, Oldenburg says, is key. The strongly feminized values of hominess and comfort provided by this type of third place stand in contrast to the more masculine notion of space intended for deep literary contemplation that Patricio works to create in Aristipo. The hominess of this type of third place becomes linked with the comfort and privacy of the home, while still being public.

[1] One of her phones. Her second phone sits charging on the chair across from me.

The Bookstores as Both an Agent and Target of Gentrification

As I previously mentioned, I spent an exorbitant amount of time at Libros del Pasaje over the course of my research. Bookstore-café hybrids are not uncommon in Buenos Aires, but I found Libros del Pasaje to be one of the more popular, for in the many hours I was there, I never saw either the bookstore or the café empty. On weekends especially, I often had to weave through the narrow spaces between the shelving and table displays made narrower still by the many customers perusing the store only to find no empty seats in the café.

When you walk into Libros you first enter the bookstore. There are window-paned doors into the café, but they are locked, and you have to walk through the entire bookstore, in order to enter the cafe from the back. The layout is well-designed, as I always spend a few minutes looking at the books before entering the café and again before leaving. The walls of the café area are painted a sky blue and the ceiling is entirely glass. There are illustrations painted along one wall and planters that are home to long, drooping ivy vines. I found the décor very aesthetically pleasing, and it contrasts well with the dark stained wood of the shelving and floor of the bookstore. It was the first independent bookstore-café I had ever been to, and I quickly became obsessed with it.

I first learned about Libros from my friend Carolina during our semester abroad in the fall of 2018. We made plans to eat lunch there and get some work done with a couple of our other friends. My host mom’s apartment was in Balvanera, a residential neighborhood with only a few bars, not many restaurants, too many textile stores to count, and one of the more concentrated Jewish communities. As it offered little in terms of nightlife, I would often find myself catching a taxi or taking the subte [subway] to Palermo, the nexus of the city’s nightlife. I loved the bookstore’s atmosphere from my first visit, and would endure the thirty-minute commute weekly to do my work there.

When it came time to find housing for my capstone research in the summer of 2019, I looked for apartments in Palermo in order to have the opportunity to live close to the nightlife and shops I had to commute to the year before. I intentionally chose an apartment that was a mere four blocks away from Libros and the bookstore became even more of a staple in my life than it had been before.

Located in northeast Buenos Aires, Palermo is the city’s largest neighborhood. Palermo was originally a residential neighborhood for working class European immigrants and their descendants and consisted primarily of factories and warehouses. Many older porteños I encountered have said that no one really went there in the past, whereas now it is known for its trendy shops and nightlife. For academic David Rosenblum (2013), the neighborhood serves as a “hotbed” of the urban development and gentrification that have been restructuring the city over the last four decades. He tracks the effects of neoliberal policy in Argentina, writing that,

In urban terms, during the years of the dictatorship and through Menem’s presidency, [Buenos Aires] transformed into a center of global business, adopting international brands and modern styles, in a process similar to that of other global cities, product of urban neoliberalism. A large growth in real estate fueled the construction of new buildings, houses, and neighborhoods. 20[1]

Rosenblum’s analysis can be applied to the new bars, restaurants, shops and clubs that constitute Palermo today as a product of the restructuring of the neighborhood. The result of the new buildings and renovation of homes, workshops, and warehouses has been the displacement of the people who had previously occupied these spaces.

While parts of the neighborhood have not been affected, the majority of local stores have been replaced by international companies and similarly-modeled local stores. This is a result of Argentina’s adoption of neoliberal policies in the 1980s and 90s which restructured the urban layout of Buenos Aires to resemble that of a “global city.” Rosenblum fits Argentina’s process into a greater global pattern, discerning that

with the impregnation of neoliberal ideology in urban spaces, similarities flourished in the structures of the biggest cities in the world. The same global businesses, products, and constructions arrived and grew in global cities, reproducing the same urban environments and spaces through great distances. 13-14

Neoliberal policy alters the demographic of both the people and types of businesses of Buenos Aires. The types of high-rise apartments, supermarkets, and businesses in Buenos Aires today are some of the essential structures that comprise the “global city.” For this reason, they render Buenos Aires familiar to international visitors who have lived in and around other cities, myself included. It is important to note that while global processes like neoliberalism are often considered impervious forces that entirely erase local culture and replace it with one that is more international, they actually occur within and adapt to the context of the local culture itself (Gibson-Graham, 1999). While Palermo has been reconstructed as a result of gentrification, changes seem to have been made with the city’s cultural values in mind. Bookstores themselves serve as a good example of this, as across time, they have been an important symbol of the city’s culture.

While many bookstores have closed as a result of unaffordable rent, the city remains the “bookstore capital of the world.” Right before I left for Argentina for my capstone, my good friend gave me a book that contained lists of the bookstores in Buenos Aires accompanied by descriptions of each and maps of the neighborhoods, with the stores’ locations marked. El Libro de los Libros: Guía de Librerías de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires[2] was vital to my research, as I looked to it to determine which bookstores to visit. The edition was from 2010, and upon going to see the bookstores in person, I found many of them had closed permanently. Indeed, a bookseller I met advised: “if you want to own a bookstore and you pay rent, forget it.” Mona spoke from experience, as before her current job, she had worked at Clásica y Moderna Libros, an 80-year-old bookstore that city legislature declared a site of Cultural Interest only six years prior. It closed as a result of the space being too expensive just last year. I met Mona at her new job at a bookstore that had opened two months prior in a residential area of Recoleta. She told me the owners were a married couple who had moved to an apartment nearby after retiring from their jobs as accountants, and decided to convert their old house into a bookstore. By owning the building, they were able to circumvent the cost of rent that drove stores like Clásica and Moderna out of business. I was able to speak to one of the owners who said that the job was, “precious for someone who isn’t very economically ambitious.” He joked about the lack of economic profit a bookstore provides, but, as a wealthy former accountant, he was of a high enough socioeconomic status that profit was inconsequential, as owning the store was more of a passion project than a business endeavor.

Despite the continuing closure of bookstores, even those recognized for their cultural significance, new bookstores continue to open. Although many of the bookstores in the guide my friend had given me had closed, I found a number of bookstores that had opened quite recently, sometime after the book’s publication. Due to rising costs in the city, bookstores that are unable to support themselves go out of business as new stores are opened by people who have other sources of income. The closure of some bookstores and subsequent opening of others serves as a clear demonstration of the patterns of gentrification in Buenos Aires. While the married couple opened their bookstore in a building they already owned, and thus are not actively gentrifying, they shed light on the conditions bookstore owners must navigate in the city, and the high socioeconomic status necessary to be able to afford to navigate them. The consumption of culture through print media like books has been essential in the Argentine state’s efforts to produce national identity (Bordat-Chauvin, 2016). The gentrification in neighborhoods like Palermo corresponds to the cultural ideals of the city, as the value of books is part of its cultural policy.

Just celebrating its fifteenth birthday, Libros del Pasaje is one of the many businesses that opened during the gentrification of Palermo. My first trip back to Libros, I was greeted by a big “15” drawn with a paint marker. Inside, to commemorate the notable anniversary, black and white pictures of authors and people I assumed have been important to Libros were hanging on the back wall. They occupied the liminal space where the bookstore ends and the café begins. To the left of the photo display, a brief history of the store was printed directly on the wall, reading:

El 18 de mayo de 2004 creamos un nuevo espacio que, sentíamos, faltaba en Palermo. Para hacerlo, elegimos uno de los típicos caserones del barrio y lo adaptamos a nuestra propuesta, rescatando su espíritu y respetando su estilo.

Desde entonces, invitamos a los lectores a nuestra casa, para ayudarles a encontrar aquellos libros que buscan o acercarles nuevas propuestas que puedan disfrutar junto a un café en nuestro bar. También organizamos charlas con escritores, presentaciones y muestras de arte.

No nos olvidamos de los más chicos y planeamos actividades que los ayuden a descubrir el placer de la lectura.

Gracias por compartir todos estos años con nosotros y ayudarnos a seguir creciendo

“On May 18, 2004, we created a new space that, we felt, was missing in Palermo. To do it, we chose one of the typical big houses of the neighborhood and we adapted it to our design while rescuing its spirit and respecting its style.

Since then, we invite readers to our home, to help them find the books they’re looking for or to introduce them to our recommendations which they can enjoy with a coffee at our bar. We also organize talks with writers, presentations, and art shows.

We don’t forget about the kids and plan activities that help them discover the joys of reading.

Thank you for sharing all these years with us and for helping us continue to grow.”

At first I found Libros’ story endearing, but as I sat with it, I became suspicious of their choice of words. What did they do exactly to “rescue” the spirit of the house and where can it be seen in the bookstore today? I took a picture of the wall from my table across the room before continuing to journal. Months later, back in the United States, I found the photo in my camera roll and sent an email to Libros asking them what they could tell me about the history of the space prior to being a bookstore, and I have yet to hear back.

The processes of gentrification transform urban spaces with the consequent displacement of the people who lived there and erasure of their legacy. Whereas many residents of Buenos Aires recall Palermo before it was gentrified, and many have lived in Palermo throughout the process that displaced so many of their neighbors, the commercial spaces and apartment complexes being established in Palermo bear little to no reference to the people whose space they now own, nor are they built for their benefit. Rather, they are intended to appeal to middle and upper-middle class tastes. The neoliberal ideology that galvanizes these processes produces “hegemonic constructions of history” that urban anthropologist Setha Low (2016) observes, “justify the political and economic control of wealthy elites and transnational corporations [and] are infamous for excluding the memory and local history of residents facing neighborhood gentrification and urban redevelopment” (77). The openings of spaces like Libros del Pasaje demonstrates how gentrification functions within the city’s cultural ideals, as the bookstore embodies the significant literary history of Buenos Aires, as opposed to the history of Palermo as a working class residential neighborhood.

The type of city that neoliberal ideology produces “... [attracts] certain sections of society and certain social groups more than others” (Rosenblum, 14).[3] Within the context of Palermo, the businesses and apartments being built are intended to appeal to a certain type of person, one with a disposable income and leisure time, like me, for example, an international student doing a semester abroad. Indeed, Libros was so attractive to me as a foreigner because of how “authentic” it felt compared to the various café chains that I had been to, despite also being a relatively new addition to the neighborhood. Libros del Pasaje appropriates the “spirit” of the old neighborhood of Palermo in such a way that it is repackaged into a cozy bookstore-café that offers an “authentic” experience of the literary tradition of the city so appealing to international tourists and people of a higher socioeconomic status.

I remember a news special I watched on el trece while sitting with my host mom at dinner about Palermo and how expensive and unaffordable it had become in the wake of the economic crisis with respect to restaurants and clothing stores in particular. Now, the reporter said, only foreigners can spend time there, and she proved her point by interviewing people from Venezuela and France who were living in the neighborhood. It’s true. A huge number of international students and travelers are living in Palermo. Over the summer, I met people from France, Ecuador, England, Venezuela, Belgium and Australia, all living in Palermo and enjoying its nightlife. One time, my Ecuadorian friend living there on a student visa told me that he met some tourists from the United States who had spent weeks, maybe even a month, in Buenos Aires, but had never left Palermo and hadn’t had any plans to do so.

While I had frequented Libros as a student abroad, coming back there as a neighborhood resident felt different. One day, when I was taking field notes there, I noticed just how many European and American students there were, sitting either alone or in groups, doing their schoolwork. I was amused by how many young white women were stationed in front of their laptops with their reusable water bottles, all doing the same thing, until I remembered I was one of them. We all sat there for hours nursing our cafés con leche, as Argentines would come in for a quick espresso or to meet up with someone and leave within the hour.

It was not until mid-July that I went to one of the free weekly talks Libros advertised on their Instagram account. The events range from educational lectures, political panels, and book clubs, which include topics such as capitalism, sex, and religion. The talks are given at the back of the store, the speakers presenting from the couch located beneath the anniversary display. I went to a presentation by the author of a newly-released book. I had seen the book on display in various bookstores, so when I recognized it in Libros’ Instagram post about the event I decided to go.

The café tables were brought into the main café area and the glass doors were shut to make room for the rows of chairs set up for the talk, closing the café-goers inside. I arrived ten minutes early and sat in the outermost chair, allowing me to rest my head on the book display that jutted out of the wall. I entertained myself by skimming through a book that interpreted the placements of Venus in the zodiac natal chart. Suddenly, feeling the stare of a woman seated in my row, I returned the book to it shelf. I had assumed she was judging my desire to learn about my Venus in Aquarius and braced myself to meet her gaze. Yet, I saw it was not me she was staring at, but the Nalgene water bottle in my bag. “Where did you buy that?”

I told Maria, a blonde woman in her fifties, that I had brought the bottle with me from the United States. She told me she was a professor of Latin American literature and had taught at several schools in the United States. I brought up my project, explaining I was interested in seeing how the bookstores of Buenos Aires may function as public communal spaces in the city today, considering their significance in the city’s cultural history. I attempted to draw the look on her face in my notebook because my project made me react the same way: eyebrows raised, eyes squinted, mouth agape. Utter confusion with a hint of frustration. I did not blame her. It was difficult to describe what my project was actually about beyond the focus being on bookstores while still doing the research necessary to figure it out.[4] She did not ask many follow-up questions, and my bruised ego and I were thankful to be free of interrogation.

Just then, Maria’s friend arrived and greeted her with a kiss on the cheek before taking the vacant seat between us. Like Maria and the rest of the people present for the talk, her friend was white, in her fifties, and nicely-dressed, wrapped in a long black trench coat. They spoke for a while about their grandchildren and Maria leaned over to tell me her friend writes books.

“Oh, qué lindo!” I exclaimed. “What are they called?”

“I’ve written many” the friend responded, and they continued chatting.

I had already felt out of place as the youngest and most casually-dressed person there, but now I was also insecure about why I was there in the first place. The talk finally began with two lengthy introductions by a man and woman who were seated on either side of the author. When the author finally spoke, she noted how glad she was to see so many loved ones in the audience. In fact, it seemed most of the audience was made up of her close friends and family, now seated with a Libros del Pasaje bag in their hands, her book showing through the translucent plastic.

At the end of the talk, the book presentation turned into a social gathering. From my corner, next to the astrology book, I watched as people greeted each other with big hugs, kissed each other’s cheeks, and spoke in little clusters throughout the bookstore. A couple of older men approached me, asking if I knew the author. In one conversation with a good friend of the author, I learned that he read “literature from all around,” naming classics from only England and the United States, “but not much Argentine literature, well, except for my friends.”

Libros del Pasaje is one of the few independent bookstores I found in Buenos Aires with enough space to accommodate such events. Later on, I mentioned the event to a bookseller at a different store who said he didn’t get the point of these presentations because it was always the author’s friends and close supporters who would show up and buy the book that night, then the books would barely sell after. He confirmed why I felt like such an outsider within the audience, even though, like everyone else, I was interested in hearing the author speak about her new book. I was not an outsider because I was younger nor from the United States, but rather because I was not a member of their social circle.

The only other talk I went to at Libros was a lecture on the relationship between psychology and literature given the following week. I found it all quite difficult to follow. The content of the talk was well within my Spanish comprehension, but the presentation was, nonetheless, inscrutable. The lecturers referenced specific authors and used complicated terminology without providing definitions or explanations. Whether intentional or not, the lecture was certainly not introductory, as only those who were already well-versed in the subject matter would have been able to keep up. Familiarity with the theories and names mentioned was necessary to appreciate the lecture. The number of people in attendance seemed to highlight the program’s inaccessibility. Whereas all of the 30 or so seats were taken at the book presentation, only around six people were present at the lecture.

Although these events are technically free and open to the public, appreciating them requires cultural capital that is unevenly distributed (Bourdieu, 1987). With respect to the lecture, the cultural capital necessary was articulated through education level; whereas, for the book presentation, the social connections to the author were key. In short, both required high levels of cultural capital, be it through education or social affiliations. In this way, the people who participate in these events possess the same middle and upper-middle class tastes that the restructuring of Palermo has been designed to reflect.

[1] Original text: “En términos urbanos, durante los años de la dictadura y a través de la presidencia de Menem, se transformó en un centro del negocio global, adoptando marcas internacionales y estilos modernos, en un proceso similar al de otras ciudades globales, producto del neoliberalismo urbano. Un gran crecimiento del mercado inmobiliario avivó la construcción de nuevos edificios, casas y barrios.”

[2] Compiled and published by Asunto Impreso Ediciones

[3] Original text: “...atrajo a ciertas secciones de la sociedad, a ciertos grupos sociales más que otros.”

[4] Not to mention I am much better at acting like I know what I am talking about in English.

Conclusion

The booksellers we have met in this essay each articulate a certain literary taste they use to position their bookstores as distinct third places within the neoliberal economy. Patricio, for instance, positions himself in opposition to mass-market literature in an effort to establish his store as a space where one can appreciate his idea of enriching literature, away from everyday life. On the other hand, the booksellers of Libros del Pasaje works to reflect their surroundings by encouraging events that appeal to the same middle to upper-middle class tastes that have gentrified the neighborhood around them and fit accordingly.

The cultural significance of bookstores in the city of Buenos Aires remains impervious to the shifts in the economy and urban landscape. It is not a question of whether processes occurring under neoliberal policy will account for the cultural significance of bookstores, as it is supported by mainstream histories of cultural value the state works to promote. Instead, the longevity of a bookstore depends on how well it fits into the urban landscape that gentrification establishes, and whether or not it can reshape itself to the middle to upper middle class ideals that the process works to design.

Although none of the bookstores discussed embodies all of the characteristics of the third place necessary for Oldenburg, they still serve as types of third places. Perhaps the most common characteristic that these bookstores lack is the idea of leveling. As a result of both social and spatial stratification, individuals tend to go to bookstores close by, meaning that they would be surrounded by people from their own neighborhoods and subsequently, people of a like socioeconomic status and similar taste formations. The bookstores do not embody a singular version of the third place.

Bookstores were a third place to me not because of my devotion to the fight against los bestsellers, nor because I was seeking refuge from everyday life. Instead, I went to bookstores to observe and to live in the familiar comfort, the meditative reprieve from city life they offer. Like the man who told me his daily visits to el Ateneo were his “sweet time,” the time I spent reading, journaling, and browsing Libros’ bookshelves was mine. I caught momentarily glimpses of other peoples’ lives, like a man making business calls with two glasses of white wine at his disposal, or another man I sat next to once who pulled out an iPad to watch an instructive synchronized swimming videos on Youtube, jotting things down in a notebook. Bookstores are a meaningful third place in cities because they embody a space that encourages a sense of calm, a break from the obligations lingering outside, a way to engage with one another through literature and conversation. Much of my time in bookstores was spent “being alone together” with a room full of strangers, in the comfort of familiar anonymity.